‘Oh, East is East and West is West, and never the twain shall meet,

Till Earth and Sky stand presently, at God’s great Judgment Seat.’

Rudyard Kipling – The Ballad of East & West.

Seventy years on, and the great continent of India no longer has that taste of colonialism lingering on the palette, except for those very few who can still remember the events of August 15th 1947, and then most likely their palette is residing in a glass of water beside their bed.

When we recount the events of WW1; a bloodbath which involved far too many virtually ignored, un-remarked upon, and brave colonial soldiers, we forget that many came from the then Indian sub-continent. As the TV presenters serve up great swathes of nostalgia, much emphasis is put on the Western forces – Australians, South Africans, Canadians and New Zealanders – who died during the Great War. The hero’s of the Verdun and other horrific WW1 battle scenes, are always presented as being white and European, although this is far from the truth.

Mountbatten with Ghandi

Moving forward in time to the 17th August 1947, and on this 70th anniversary, we now see sepia films showing the final salutes of men and women – often in enormously baggy and dated military uniforms – who are wondering if leaving India is the right thing to do, and worrying about what life might have in store for them back in a war damaged Britain. A country that is also trying to re-emerge into an equally uncertain future, together with the rest of poor decimated Europe.

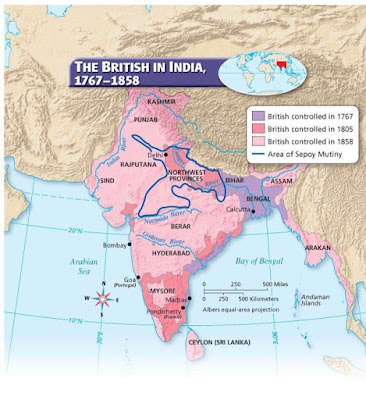

For over three hundred years Britain had been the policeman of India, what was soon to become the State of Pakistan and ultimately, an emerging Bangladesh. Did the politicians of the day eulogize over these brave and ignominiously forgotten Indian soldiers, who fought for a foreign mother country, some thirty years before? We shall never know it was all too long ago, but I doubt it!

Most of us see the post war years in rather theatrical terms, and in the shires and the home counties of England – especially in the 50s and 60s – one often came across slightly dotty relatives who talked incessantly about their time in India as being the best time of their life.

Surrounded in their new homes, by reminders of years spent on the equator – the pith helmets, the Indian swords and engraved matchlocks – the many sided tables with ivory, and mother of pearl marquetry, would often support a well brewed cup of Darjeeling tea. Then there were the photographs of ferocious looking Colonels – their foot on the head of an equally ferocious looking, but somewhat dead tiger – at a family get-together, where as a child I was introduced to the wonders of cold curry, tales of the Berkshire Regiment, and the redoubtable Uncle John.

Back then, in the sometimes jaded reality of back street Brighton, in a world of seaside boarding houses – the subject of plays by Terrence Rattigan or John Osborne – the fifties and sixties seemed to be populated by hopeless people; old majors or retired district commissioners, all of whom found it difficult to adapt to their new home environment. Dear old Col. Hillary Hook couldn’t even boil an egg boil a kettle, let alone switch on a light.

Often born to parents who had lived all their lives in India, there were families who’d lived and survived there, for generations. Lives, occasionally interspersed with the odd visit to an English public school, the very occasional university, or generally to Sandhurst, it was then back to India to work in some colonial capacity.

In their minds eye, India came to be as much theirs as the indigenous population itself, because British blood had been spilt on the ground of this their chosen home, and as simple as that.

But they were also obnoxious, they were snobs, they were xenophobic, and they were unquestionably spoilt by their Indian hosts, and nevertheless – even to this day – they remain severely misunderstood.

Emanating from the newly found and emerging middle classes of the early nineteenth century, the sons and daughters of successful traders and manufacturers, these newly found colonialists, had often been precluded from gentile society in their British homeland – trade was a nasty word up until the 1950’s – and India proved to be the perfect alternative.

Surrounded by the trappings of wealth, the Maharajas paid lip service to their so called protectors, but they too indulged in the imported social snobbery, and anglicised their views, often by adopting the public school, and elitist attitudes of their colonial cousins, into the bargain. Eton, Harrow, and smart Indian Regiments were all the rage, and a kind of effete Indian aristocracy emerged on the racecourses of Ascot and Epsom and the polo-grounds of Hurlingham and Windsor; but not for long. By going forward in time, once more, we now know why.

The scratched and distressed sepia films show the lines of people, but not their thoughts. Tears and smiles must have mingled with nostalgia, and although some were sorry that they were leaving, others were not. Gandhi’s salt march had done the trick, Mountbatten had handed India back with as much dignity as he could muster and India was left to denude its own reality, and make the railways run on time.

Back in the UK sports masters were called Major this, the school bursar was called Colonel that, and the grounds man was called Sergeant something or other too, which was certainly the case when I first went to school.

As I write in the present day, I can still recall my aging aunts and uncles, small carved ivory elephants in glass cases, the aroma and sounds of an India still lingering in a photograph album, and a nameless dog, obediently sitting on the veranda of some long forgotten bungalow. And, although the shadow of this much loved past still hides behind the glossy brochure of a new modern and thriving India, I am afraid, that what I remember really doesn’t matter anymore.

Gandhi with Tagore

Today the talk is of computer technology, and India’s high profile nuclear tests, none of which are approved of by the great powers. Now medium range rockets wobble on their launching pads and die – with disappointed looks from ambitious Indian onlookers – and young Indians, once the scourge of immigration officers in the UK, are now the invited guests of a burgeoning electronics industry; short of manpower.

No longer destined for the sweat shops of Huddersfield or Leeds, nor selling assorted silks from a market stall in Brick Lane or Southall, these young Indians now represent a new well educated middle class, destined for the wine bars of Dover Street and trendy Covent Garden. Oh, how the world has changed.

We find the India of today simultaneously seething with the extremes of poverty and great wealth, with – one must admit – a strong European demeanour. Gone are the cliches of the past – the Star of India Restaurant and the Bombay Brasserie, are now in the Michelin Guide – and pandering to the spoilt, the overpaid, and the trenchermen of a high cholesterol multicultural London.

Most of us have completely forgotten how it all began, although during recent time spent in India, I met many who were happy to attest to an amicable colonial past. But how did young Indians feel about their most recent past? Well, they seemed to have forgotten about it too!